Fair Food, Protecting an Unseen Essential Workplace

“We are a community that is accustomed to fighting,” says Lupe Gonzalo. “For years—for decades—that’s what we’ve been doing. We’re ready to take on another struggle.”

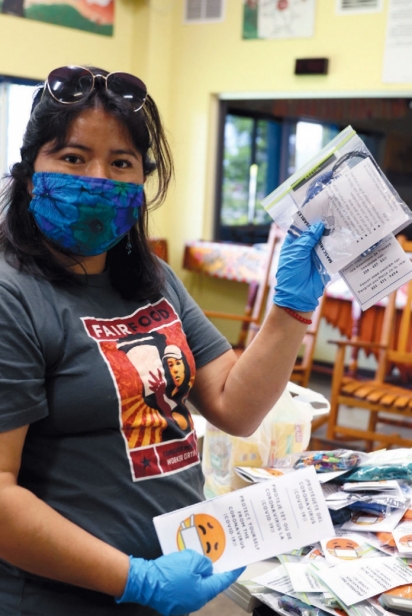

Speaking to Edible Sarasota through a translator, her voice is steady and clear as she describes fear and hardship experienced by Florida’s migrant farmworkers during the coronavirus pandemic’s escalation. A senior staff member for the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW), Gonzalo is a leader in the advocacy group’s Fair Food Program (FFP), which fights ceaselessly to raise pay, end wage theft and abuse, and secure humane working conditions for farmworkers.

The arrival of COVID-19 added a new threat to the health and safety of Florida’s farmworkers, a community already stressed by low income, barriers to healthcare and social services, and other systemic inequities. Their plight is all but invisible to most Americans, but here’s the reality: If farmworkers stop working, we stop eating the tomatoes, berries, watermelons, and everything else they harvest by hand from Florida’s fertile fields.

The Florida government deemed farmworkers essential, but a response to supply COVID-19 testing and contact tracing came slowly and unsuited to serve a rural, largely Hispanic farmworker population. In June, the Tampa Bay Times reported that some of the state’s first testing sites in agricultural communities had opened, but the growing season had already ended, and many workers had moved on to harvests north of Florida.

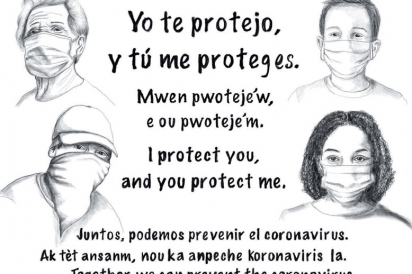

Fortunately, humanitarian organizations had already recognized the grave risk coronavirus posed to the vulnerable farmworker population in Immokalee. Doctors Without Borders stepped in to provide mobile testing sites and facilitate a public health education campaign in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole. In mid-July, Partners in Health began training locals to become community health workers: trusted, familiar faces who share vital information, including how to obtain social services such as rental assistance, and empower their neighbors to fight the spread of disease.

As Florida’s harvest season ramps up, the ability to physically distance at home and at work, as well as isolate the sick, remain thorny challenges for the farmworker community. Gonzalo says that while access to testing has improved, the CIW must keep pressing the state and local health department for more robust contact tracing and a solution to isolate farmworkers who fall ill. As it calls for Florida health authorities to protect the essential agricultural workforce, the CIW continues its own work to inform and safeguard its community.

“What we have seen is really no effort to get information to our community in particular about what we can do to protect ourselves,” Gonzalo says. “So we’ve gone around to get the word out on posters in different languages all over town, in the camps and trailer parks where workers live, every blank wall we could find.”

The CIW also leverages its low-power FM radio station to interview health experts and broadcast COVID-19 prevention guidelines. They distribute donations of masks and other personal protective equipment. They have also tapped into their relationships with FFP-affiliated growers to promote worker safety in the fields through mask policies, extra handwashing stations, and more buses to allow for physically distanced transportation.

“We know that we have to continue to get out, educate, and talk to people to inform them of what’s going on and what they can do,” Gonzalo says. “Because if we don’t do it, we know there’s nobody else who will do it for us.”

Julia Perkins of the CIW contributed to reporting for this article with translation.

Make a donation to support the ongoing efforts of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers and Partners in Health to prevent the spread of COVID-19 among Florida’s farmworkers. Give online at CIW-online.org and PIH.org